How to mount a LUKS encrypted Linux drive in Windows

Become the world’s top super hacker with this one weird trick

This is kind of fun, but probably no one will need to do this ever. But the point is you can! So why not? Anyway, suppose you have an encrypted Linux drive and you want to mount it in Windows for whatever reason. Just follow along.

Install Windows Subsystem for Linux 2

WSL 2 allows you to run a virtualized Linux environment that integrates tightly with the Windows OS. To install it, search for "Turn Windows features on or off" in the Start menu and click the shortcut to open the Settings pane. Scroll down towards the bottom and check the box for "Windows Subsystem for Linux". Then click "OK" to install WSL 2.

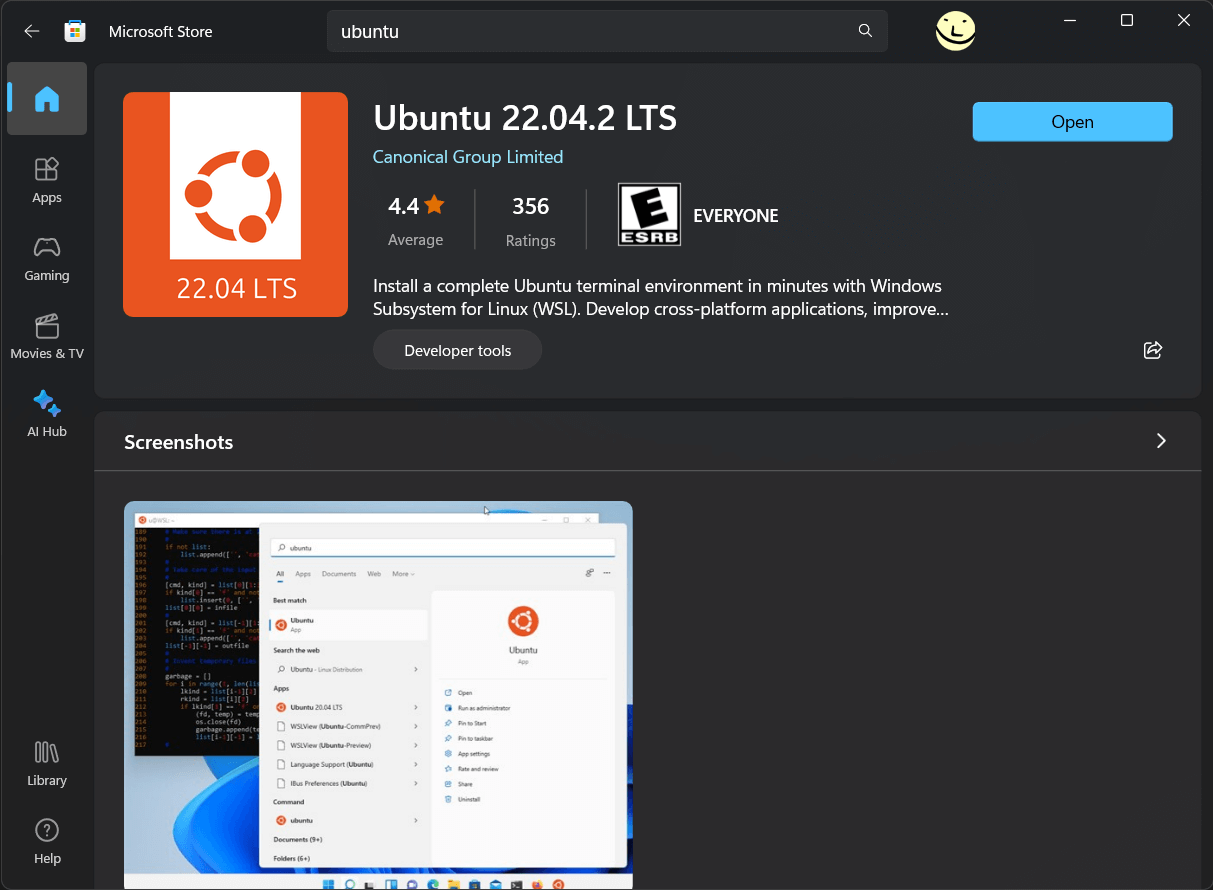

Open the Microsoft Store app and install Ubuntu Linux 22.04 LTS

This is trippy as hell. Ubuntu Linux on an App Store? We have entered the end times indeed.

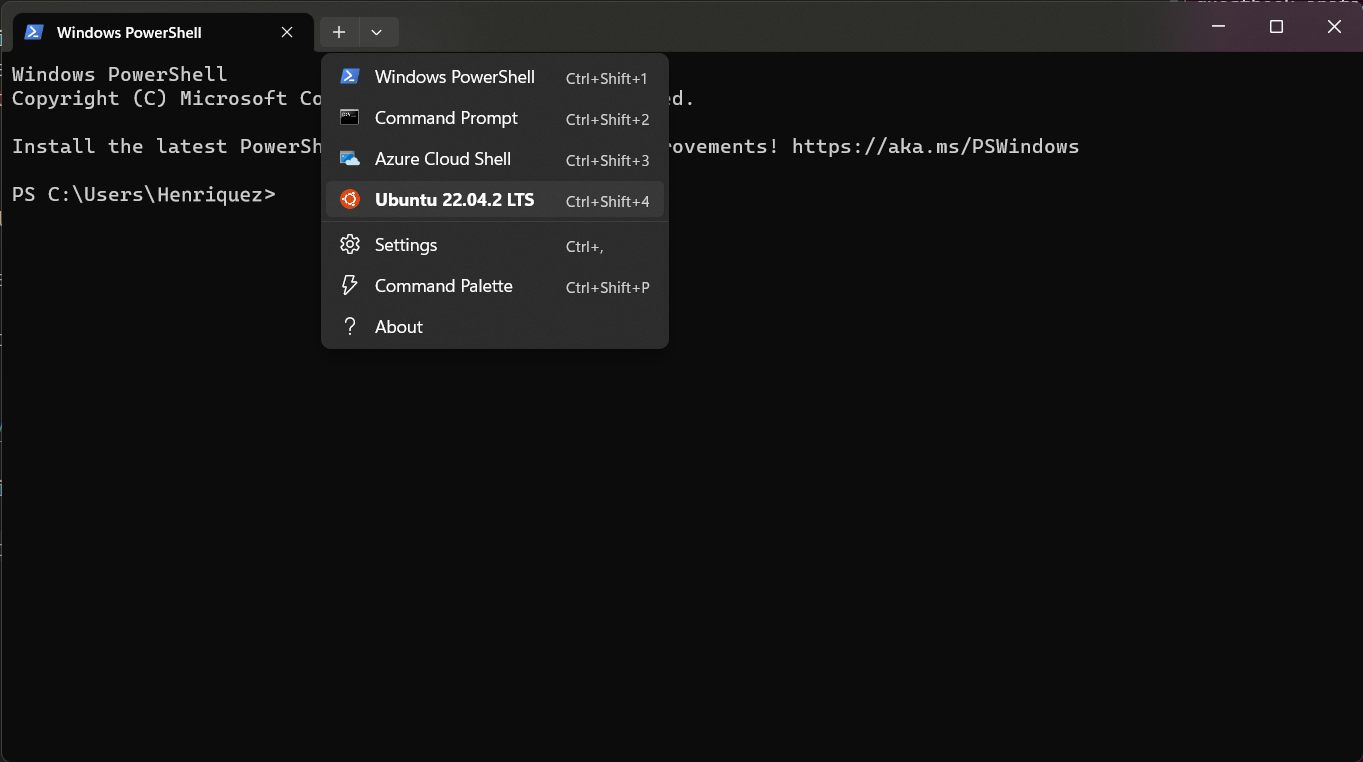

Confirm it worked by opening Linux in Windows Terminal

Start the Terminal app, which should be pre-installed. By default it will probably open to a Powershell or Command Prompt. Click the dropdown arrow on the tab bar and you should see "Ubuntu 22.04.2 LTS" or something similar in the dropdown menu. Click it to start Linux!

Run an Administrator Powershell and give WSL 2 access to your physical drive

These instructions are adapted from Microsoft's own documentation so check that out if you need help. Basically, open a new Powershell as Administrator (right click the shortcut and then "Run as administrator").

List your physical drives by entering:

GET-CimInstance -query "SELECT * from Win32_DiskDrive"The command should give you output similar to the following:

DeviceID Caption Partitions Size Model -------- ------- ---------- ---- ----- \\.\PHYSICALDRIVE3 Samsung SSD 980 PRO 2TB 1 2000396321280 Samsung SSD 980 PRO 2TB \\.\PHYSICALDRIVE0 WD_BLACK SN850X 4000GB 3 4000784417280 WD_BLACK SN850X 4000GB \\.\PHYSICALDRIVE1 Samsung SSD 970 PRO 512GB 1 512105932800 Samsung SSD 970 PRO 512GB \\.\PHYSICALDRIVE2 WDBRPG0020BNC-WRSN 1 2000396321280 WDBRPG0020BNC-WRSNSo, one of the DeviceIDs in the output should map to your LUKS encrypted Linux. Suppose for example it was

\\.\PHYSICALDRIVE3, then you can give your WSL 2 environment access to that drive with the following commmand:wsl --mount \\.\PHYSICALDRIVE3 --barePROTIP — If you need to do this a lot, you can put that command in a .bat file and run it (as Administrator) anytime you want to mount the drive in WSL 2.

Find your encrypted drive in your WSL 2 shell

Go back to your Terminal with the Ubuntu Linux shell running, and if everything worked, you should be able to find your encrypted drive with the following command:

lsblk -lThe command should give you output similar to the following:

NAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINTS sda 8:0 0 363.3M 1 disk sdb 8:16 0 8G 0 disk [SWAP] sdc 8:32 0 1T 0 disk /snap /mnt/wslg/distro / sdd 8:48 0 2T 0 disk sdd1 8:49 0 2T 0 partIn this example the

sdd1identifier maps to the encrypted partition on your physical drive.Decrypt and mount the encrypted drive

You will need a package called cryptsetup if it's not installed. From your Linux shell, enter

sudo apt install cryptsetupif needed.Now you can decrypt the volume by entering (for example):

sudo cryptsetup luksOpen /dev/sdd1 samsung_980_pro^ The name you put in the last argument of that command is any arbitrary name you want to assign the drive in the device mapper. Just be sure that you use the correct device name for the encrypted partition listed from lsblk (in this example

/dev/sdd1).Once it's decrypted, you can mount the drive with the following command(s):

sudo mkdir /mnt/my_encrypted_drive(if needed)sudo mount /dev/mapper/samsung_980_pro /mnt/my_encrypted_drive

Obviously you can customize the names and mount location however you see fit.

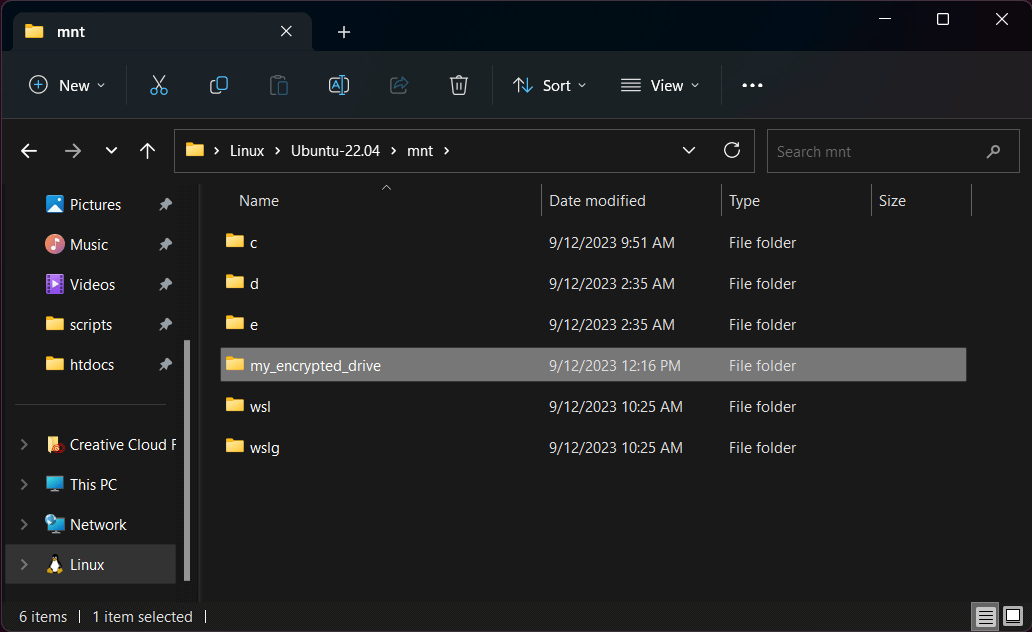

Now you can access your encrypted drive from Windows Explorer!

Open a new Explorer window and scroll down the left sidebar until you see "Linux." Click this and you'll be able to browse the filesystem from your Ubuntu 22.04 installation. Simply navigate to

/mnt/my_encrypted_driveor wherever you mounted the drive, and you'll have access to your encrypted volume!

One nice use case for this...

Having an encrypted drive is just a good idea in general. If your computer is lost or stolen you can keep your private files protected and not worry so much about identity theft or any other bad outcomes from people maliciously accessing your files. Many Windows computers ship without any kind of drive encryption, and Microsoft's own BitLocker disk encryption is only available in "Pro" editions of Windows.

Speaking of BitLocker, who can even trust that shit? It's a closed source system and Microsoft can swear up and down that it's safe and secure, but for all anyone knows it's backdoor'ed six ways from Sunday. By using Linux LUKS drive encryption in Windows, you at least have open source and provable security. Just make sure your passphrase is strong enough and you're good to go!